Everyone wants that big win. As marketers and conversion rate optimization experts, we all want to report that bazillion percent conversion rate improvement to our bosses and clients. If you have ever run a CRO experiment, you’ve likely experienced failure more often than victory. In fact, seven out of eight experiments fail to ever produce statistically significant results, yet we typically only read about success stories and those big wins.

Failure, we are taught from a young age, is bad. It’s the worst, actually. Failing is demoralizing and frustrating. A failed experiment can also be quite costly and lead to concerns over lost clients and revenue. The psychological effects of failure can be so detrimental that you fail to succeed as a result of your fear of failure. This may be one reason 48% of marketers who use landing pages don’t run experiments to optimize them.

The shame associated with failure also often leads to the dismissal of results from failed experiments. But, sometimes the best place to learn is from failure — we just need a way to decode those hidden “teachable moments.” We need a method for deducing exactly what those lessons are and how they can improve our chances of future success.

Don’t Be So Hard on Yourself

So, you had a question, designed an experiment and formulated a hypothesis, and it was not supported. First, it is important to note that you did it. You risked what many are not will to risk.

In a 2012 study of Fortune 1000 marketers, conducted by the Marketing Leadership Council of the Corporate Executive Board, only about 50% of the respondents agreed with the statement, “My team accepts that some experiments must fail in order for us to learn from them.”

You are bolder than 50% of Fortune 1000 marketers. Secondly, you should know that you can definitively disprove something, but it is impossible to prove or confirm a hypothesis, only to support it. Whether or not your hypothesis was supported, the experiment added to what you know about your initial question, and there are always more questions to answer.

And even though the results of your failed experiment don’t support your hypothesis, you have still created knowledge. You can now exclude your initial hypothesis from the possible ways to answer your question; you know now, definitively, that particular solution doesn’t work.

Thomas Edison explained it best when he said, “I haven’t failed. I’ve found 10,000 ways that didn’t work.”

It is understandable that you’d be disappointed to have a hypothesis that you are excited about disproved, but it is important to keep in mind that you are still one step closer to the most reasonable explanation. “No” can be an important answer, as long as you follow it with “what next?”

Why Does an Experiment Fail?

When that experiment doesn’t go as planned, you may wonder if you made a mistake somewhere in your methods that caused these results. An experiment can fail for any number of reasons. If you break it down and analyze the anatomy of the failure, you’ll most likely find the reason will fall into one of two categories, or even a little of both:

1. Failure in preparation

Poor research

With anything else, you will find that you get out what you put in. If your test was based solely on aesthetics, best practices or intuition and not informed by research of customer values or needs and analysis of historical data, then your test is automatically at risk of failing.

Proper research for your experiment design, including user testing, eye tracking, heat and click mapping, and Google Analytics and marketing automation data, will set you up for a successful outcome.

The more targeted and strategic you can make your hypothesis, the more likely it’ll be to have a positive impact on conversions.

Weak or nonexistent hypothesis

A solid test hypothesis goes a long way in keeping you on the right track and ensuring that you’re conducting valuable marketing experiments that generate lift as well as learning.

The test hypothesis is an educated guess that guides the design of your experiment and variation(s). It defines what you want to change and the impact you expect to see from making that change.

Build a hypothesis off of this basic formula:

By changing ______ into ______, I can get more prospects to ______ and thus increase ______ .

Wrong test method

Sometimes, small changes, like testing 41 shades of blue (like Google has been known to do), aren’t going to have a significant impact, nor will they be tests worth running. Multivariate testing is a great option to help identify the effects small changes can have on conversion rates in relation to each other, but it requires a large sample size. A/B/n or split tests, on the other hand, allow you to change the whole page, giving you license to test more freely and make all the changes you need in order to create a high converting page. However, with this method, you won’t know what feature of the variation page is responsible for the page outperforming the original.

Ready for More Conversion-Boosting Tips?

Join the worldwide community of conversion optimizers at ConvCon 2017!

2. Failure in execution

Premature selection

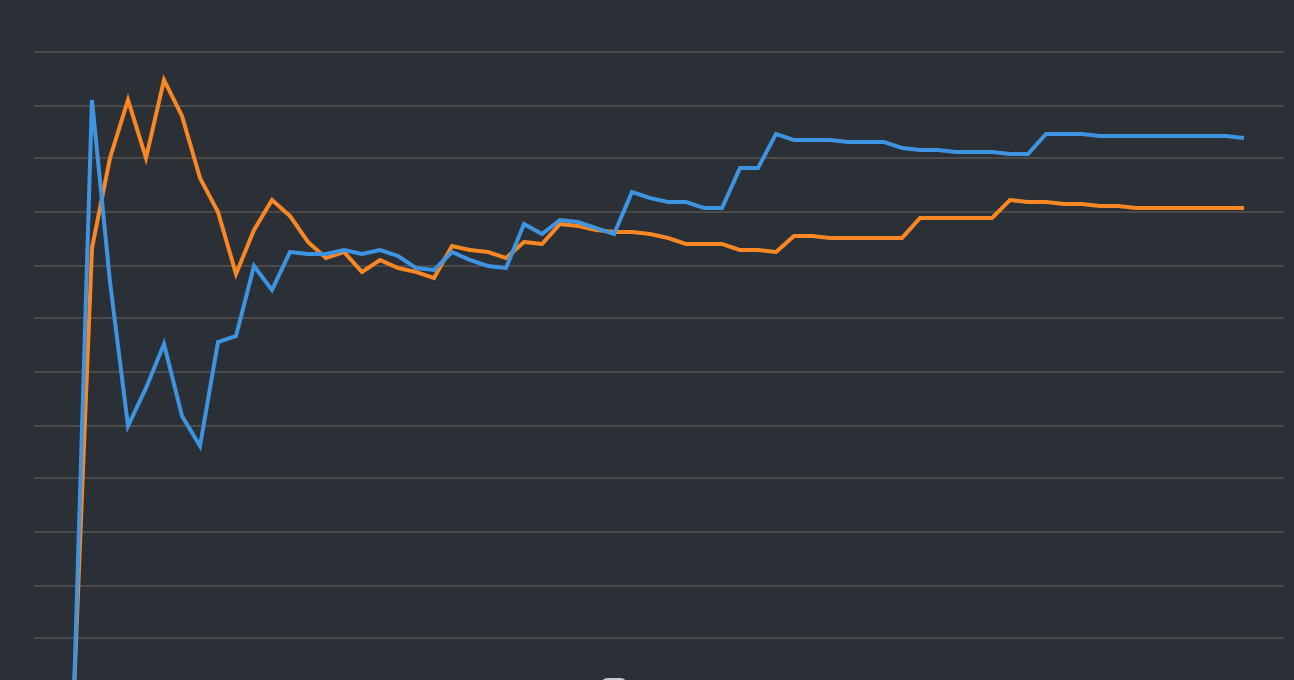

For a number of reasons, a webmaster or marketer will end an experiment early,, but often, it is because they are so excited about the initial few days of results that they assume that a given variation page is the clear winner and feel confident that there is no way that the original can outperform it.

Fear of exposure

Another common reason is that they see the failing variation bleeding revenue and leads, and they believe the best way to counteract that is to amputate, and quickly. You can avoid increased exposure by using weighted split testing. Split tests don’t have to be implemented as a 50/50 split of your existing traffic. If you have enough traffic, you can reach statistical significance with an 80/20 split, or even a 90/10 split where more traffic is sent to the “safe” page.

Lack of prioritization

Choosing to test a page with low traffic or conversion potential can cause the experiment to run too long and potentially never reach statistical significance. Use Visual Website Optimizer’s A/B Split and Multivariate Test Duration Calculator to see if your test results are at risk of being affected by seasonality or stagnation before they become statistically significant.

How Do You Identify Opportunities from Failures?

Optimization is an ongoing process, and the best results can come from an iterative process. If your initial test was not executed properly, that’s a simple fix – see above. If your hypothesis was not supported, go back to the drawing board and hypothesize a new answer to the question and way to test it.

Begin researching a new hypothesis by diving into analytics. Better data will help you identify a better hypothesis, so don’t be afraid to analyze data from every source possible: Google Analytics, customer interviews, surveys, heat and click maps, and user testing to get a full picture.

Look at secondary metrics and goals

Did your primary goal fail but you had an unexpected win with another goal? Did you decrease click-through rate but increase time on page? See what metrics you can use in your next iteration. Not every metric matters, but you can sometimes find insight in the least obvious place.

Look at user behavior, including heat and click maps

Were users distracted by an element on the page or was there information hidden in a tab that you can move to the front?

Segment your users

Did your test fail for just one segment or across all users, platforms and channels?

Ask the right questions

- Why are you running a test?

- What is the problem you’re trying to solve?

- Why is this happening?

- What is the goal? Success metric?

- Is this the right metric?

- Ask how much potential for lift does this testing opportunity actually have?

- How important is the page you are trying to test?

- How many visitors will be impacted by the test?

- Who are the visitors who will be impacted?

- Are these the same visitors experiencing the problem?

- Is there enough traffic volume?

- What is the cost of the traffic?

- What is the quality of the traffic?

- What is the impact on ROI?

- How easy is it to test the page in question?

- What are the barriers to testing?

- How long will it take to conclude this test?

Embrace Failure and Run Another Test

Landing page testing produces concrete evidence of what works in your marketing. To learn what your customers actually want, you can’t be afraid to test — you shouldn’t ever test without a plan or expect every test to win. Optimization is an ongoing process and the best results can come from an iterative process. Some of the best test results I have had were follow-up tests from failed experiments. Hold comfort in that sometimes the greatest lessons can be learned by getting it wrong.

About the Author

Jenny Knizner is the Director of Marketing and Creative Services at Marketing Mojo. She has a BFA in Graphic Design and a background in project management and design for higher education non-profit, small business, and medical publishing. She has a passion for marketing and brings a creative eye and an analytical mind to her optimization and design approach, leveraging her expertise in design strategy, project management, and conversion optimization to develop well-crafted, intuitive user experiences that lead to improved demand generation.

Jenny Knizner is the Director of Marketing and Creative Services at Marketing Mojo. She has a BFA in Graphic Design and a background in project management and design for higher education non-profit, small business, and medical publishing. She has a passion for marketing and brings a creative eye and an analytical mind to her optimization and design approach, leveraging her expertise in design strategy, project management, and conversion optimization to develop well-crafted, intuitive user experiences that lead to improved demand generation.

717 798 3495

717 798 3495